Dismantling Disease

08-01-2016

Purdue Researchers Unravel Ticks' Impacts on Human Health

By Natalie van Hoose - Published May 12, 2016

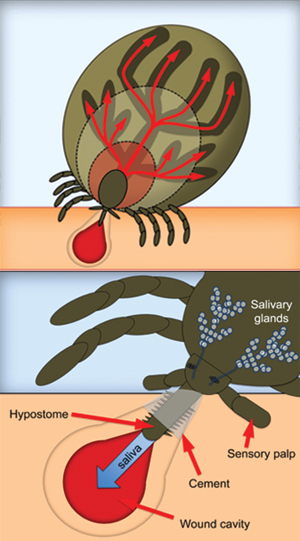

Ticks are powerful vectors of disease. Armed with barbed mouthparts and sophisticated spit, they employ strategies that have served them for millions of years—stealthily hitching onto a host, slicing through its skin to feed on blood, and regurgitating and secreting salvia potentially spiked with pathogens.

Ticks transmit a wider variety of bacteria, viruses and parasites than any other arthropod, but they're often underappreciated as vectors. The pathogens ticks pass to humans and animals can cause severely debilitating and sometimes deadly illnesses, and infection is hardly rare. Lyme disease is the most common vector-borne disease in North America, affecting an estimated 300,000 people annually, and potentially lethal diseases caused by ticks include Rocky Mountain spotted fever, Powassan virus and flaviviruses.

But tick research has long lagged behind that of other vectors such as mosquitoes.

Purdue University medical entomologist Cate Hill is changing that.

In February, an international team of nearly 100 scientists led by Hill unleashed seven papers on tick genetics, including the complete genome sequence of the deer tick, the species that transmits Lyme disease. The publications are the culmination of a decadelong effort to equip scientists with desperately needed tools to advance the study of ticks and tick-borne diseases.

"The genome provides a foundation for a whole new era in tick research," says Hill, principal investigator of the genome team and Showalter Faculty Scholar.

With the code behind fundamental tick biology, researchers can begin to investigate two crucial questions: What makes ticks such successful parasites, and why are they so adept at vectoring a mind-boggling array of pathogens?

"Now we've got the script to help us work out what proteins the tick is making, what they do and how we can exploit them to control ticks and tick-borne diseases," Hill says.

Ticks Can Change Your Life

Few people understand ticks' ability to hijack human health better than southern Indiana resident Jacqueline Duncan.

Duncan, a 46-year-old insurance agent in Rockport, began to suffer mysterious fainting spells in the spring of 2015, but doctors brushed off the symptoms as dehydration from an earlier surgery. She bumped up her intake of liquids, but her condition worsened. One night, after returning from the emergency room full of hydrating fluids, she slumped helplessly to her hallway floor. She couldn't stay conscious.

Duncan's physician, Susan Martin, ran extensive tests and took "a truckload of blood," but everything came back normal.

It wasn't adding up.

Then Duncan mentioned the ticks. She often came off the golf course or her woodland property with dozens of tiny ticks studding her ankles, and she distinctly remembered the large lone star tick she plucked off her abdomen in April and the wound it left behind—itchy and slow to heal.

Martin started her on a regimen of antibiotics and ordered a full tick panel. Duncan tested positive for Rocky Mountain spotted fever, Lyme disease and a Lyme-related heart arrhythmia.

Antibodies curbed RMSF and Lyme, but her bouts of unconsciousness persisted.

When further tests indicated she had developed allergies to beef, pork and cow's milk, Martin had Duncan's blood tested for alpha-gal allergy, a newly described disease with a suspected link to the lone star tick. The blood sample showed soaring levels of antibodies to the carbohydrate alpha-gal, more than 220 times the normal level.

A Hair-Trigger in the Body

While alpha-gal allergy is still poorly understood, some researchers think the condition arises when your body mounts an immune response to alpha-gal, transmitted to your bloodstream via a tick bite. The cocktail of compounds in tick saliva could play a role in priming the body to attack alpha-gal if it appears again.

The hitch is that alpha-gal is a naturally occurring carbohydrate in red meat and products that contain mammal-derived ingredients. Once your body has produced high levels of antibodies to alpha-gal, the simple act of eating a cheeseburger, drinking a cappuccino or swallowing a Tylenol capsule could spring anaphylactic shock.

No treatment for the allergy exists. The only recourse is to strictly avoid foods and products with ingredients that could trip the delicate wires of the body's immunology.

For Duncan, this means sticking to a diet of fresh produce, poultry and seafood, eschewing dairy products and skipping soft drinks. But the fear of accidentally ingesting alpha-gal follows her everywhere. The disease has also made her hypervigilant about protecting herself and her loved ones from ticks.

"I gave everybody bug spray for Christmas," she says.

Reports of the peculiar allergy are popping up all over southern Indiana and western Kentucky, the heart of lone star tick territory.

Duncan reached out to Hill in January, hoping to further awareness of the allergy.

"I would feel so much better knowing Purdue is working on this," she wrote. "Is there any way to get something going?"

Hill was struck by her story.

"Jacqui's case really highlights the breadth of things ticks can do and the scope of their impact," she says. "Lyme and Rocky Mountain are serious diseases. Jacqui tested positive for both and has also developed an allergy that could be tick-related. It's really stunning and scary."

New Institute to Tackle Dimensions of Disease

For Hill, Duncan's condition represents the type of multifaceted problems targeted by a new research consortium, the Purdue Institute for Inflammation, Immunology and Infectious Diseases, or PI4D.

Research has evolved a far more comprehensive approach to the biological dimensions of disease over the past decade, and the launch of PI4D reflects this paradigm shift. The institute will unite scientists from multiple fields to work on disease issues, making links between disease agents and the body's complex response.

"We're realizing that there is much more to be learned about the interconnections between infection, the health of the immune system and the body's allergic and inflammatory responses," says Hill, a member of PI4D. "In order to better understand the complexities of human disease, we need to be studying these disease states collectively."

Understanding the interplay between tick saliva and tick-borne pathogens and how they together manipulate the immune response requires a diverse expertise.

"Talking with Jacqui highlights for me the need for a team of researchers to address these kinds of health issues: an infectious disease specialist, a vector biologist and an immunologist," she says. "That's exactly what PI4D will bring."

Richard Kuhn, director of PI4D and co-author of the tick genome study, says the institute will not only study how diseases make us sick but will also develop tools to identify diseases faster so that patients like Duncan can be treated as quickly as possible.

"PI4D will bring together faculty who are pursuing new drug therapies and potential protective measures such as vaccines," says Kuhn, professor and head of the Department of Biological Sciences. "This combination of basic and applied research should translate into practical solutions to current and future disease challenges."

In the meantime, Duncan's story has Hill itching to take up her tick-flushing nets and head south. Rockport lies in an area of the state that could be home to multiple species of medically important ticks, and it's crucial that residents and doctors alike be able to identify them and watch for symptoms of disease and allergies.

"Jacqui is really fortunate that her doctor was able to connect the dots between her condition and the tick bites and then conduct the appropriate diagnostic tests," Hill says. "In turn, it's vital that scientists are sampling tick populations around the country to better understand the distribution of tick species and which pathogens they may be carrying. We at Purdue have an important role to play in communicating this information to the public and to health specialists so they can develop region-specific health care recommendations."

Related Links

Tick genome reveals inner workings of a versatile blood-guzzler