Purdue scientists reveal how bacteria build homes inside healthy cells

12-20-2011

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. — Bacteria are able to build camouflaged homes for themselves inside healthy cells - and cause disease- by manipulating a natural cellular process.

Purdue University biologists led a team that revealed how a pair of proteins from the bacteria Legionella pneumophila, which causes Legionnaires disease, alters a host protein in order to divert raw materials within the cell for use in building and disguising a large structure that houses the bacteria as it replicates.

Zhao-Qing Luo, the associate professor of biological sciences who led the study, said the modification of the host protein creates a dam, blocking proteins that would be used as bricks in the cellular construction from reaching their destination. The protein "bricks" are then diverted and incorporated into a bacterial structure called a vacuole that houses bacteria as it replicates within the cell. Because the vacuole contains materials natural to the cell, it goes unrecognized as a foreign structure.

"The bacterial proteins use the cellular membrane proteins to build their house, which is sort of like a balloon," he said. "It needs to stretch and grow bigger as more bacterial replication occurs. The membrane material helps the vacuole be more rubbery and stretchy, and it also camouflages the structure. The bacteria is stealing material from the cell to build their own house and then disguising it so it blends in with the neighboring cellular structures."

The method by which the bacteria achieve this theft is what was most surprising to Luo. The bacterial proteins, named AnkX and Lem3, modify the host protein through a biochemical process called phosphorylcholination that is used by healthy cells to regulate immune response. Phosphorylcholination is known to happen in many organisms and involves adding a small chemical group, called the phosphorylcholine moiety, to a target molecule, he said.

The team discovered that AnkX adds the phosphorylcholine moiety to a host protein involved in moving proteins from the endoplasmic reticulum of the cell to the cellular destinations. The modification effectively shuts down this process and creates the dam that blocks the proteins from reaching their destination.

The bacterial protein Lem3 is to reverse the modification of the host protein at places like the bacterial vacuole to ensure that the protein "bricks" are free to be used in creation of the bacterial structure.

This study was the first to identify proteins that directly add and remove the phosphorylcholine moiety, Luo said. "We were surprised to find that the bacterial proteins use the phosphorylcholination process and to discover that this process is reversible," he said. "This is evidence of a new way signals are relayed within cells, and we are eager to investigate it."

The team also found that the phosphorylcholination reaction is carried out by a specific structure on the protein called the Fic domain. Previous studies had shown this site induced a different reaction called AMPylation. It is rare for a domain to catalyze more than one reaction and it was thought this site's only responsibility was to transfer the chemical group necessary for AMPylation, Luo said.

"Revealing that this domain has dual roles is very important to identify or screen for compounds to inhibit its activity and fight disease," he said. "This domain has a much broader involvement in biochemical reactions than we thought and may be a promising target for effective treatments."

During infection bacteria deliver hundreds of proteins into healthy cells that alter cellular processes to turn the hostile environment into one hospitable to bacterial replication, but the specific roles of only about 20 proteins are known, Luo said.

"In order to pinpoint proteins that would be good targets for new antibiotics, we need to determine their roles and importance to the success of infection," he said. "We need to understand at the biochemical level exactly what these proteins do and how they take over natural cellular processes. Then we can work on finding ways to block these activities, stop the infection and save lives."

A paper detailing their National Institutes of Health-funded work is published in the current issue of the Proceedings of National Academy of Sciences. In addition to Luo, Purdue graduate student Yunhao Tan and Randy Ronald of Indiana University co-authored the paper.

Luo next plans to use the bacterial proteins as a tool to learn more about the complex cellular processes controlled by phosphorylcholination and to determine the biochemical processes role in cell signaling.

Writer: Elizabeth K. Gardner, 765-494-2081, ekgardner@purdue.edu

Sources: Zhao-Qing Luo, 765-496-6697, luoz@purdue.edu

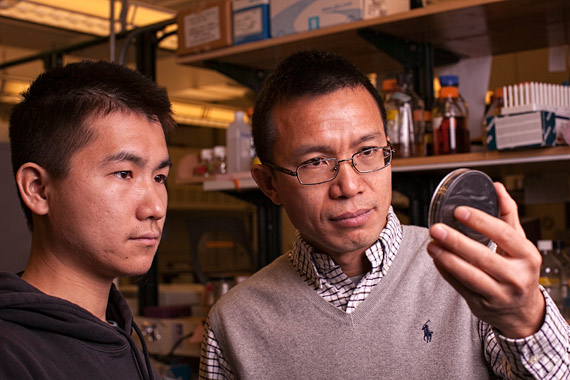

PHOTO CAPTION:

Purdue associate professor of biological sciences Zhao-Qing Luo, at right, and graduate student Yunhao Tan look at the growth of Legionella pneumophila bacteria in a petri dish. (Purdue University photo provided by Laurie Iten and Rodney McPhail)

A publication-quality photo is available at http://news.uns.purdue.edu/images/2011/luo-legionella.jpg

ABSTRACT

Legionella pneumophila regulates the small GTPase Rab1 activity by reversible phosphorylcholination

Yunhao Tan, Randy J. Arnold, and Zhao-Qing Luo

Effectors delivered into host cells by the Legionella pneumophila Dot/Icm type IV transporter are essential for the biogenesis of the specialized vacuole that permits its intracellular growth. The biochemical function of most of these effectors is unknown, making it difficult to assign their roles in the establishment of successful infection. We found that several yeast genes involved in membrane trafficking, including the small GTPase Ypt1, strongly suppress the cytotoxicity of Lpg0695(AnkX), a protein known to interfere severely with host vesicle trafficking when overexpressed. Mass spectrometry analysis of Rab1 purified from a yeast strain inducibly expressing AnkX revealed that this small GTPase is modified posttransationally at Ser76 by a phosphorylcholine moiety. Using cytidine diphosphate-choline as the donor for phosphorylcholine, AnkX catalyzes the transfer of phosphorylcholine to Rab1 in a filamentation-induced by cAMP(Fic) domain-dependent manner. Further, we found that the activity of AnkX is regulated by the ot/Icm substrate Lpg0696(Lem3), which functions as a dephosphorylcholinase to reverse AnkX-mediated modification on Rab1. Phosphorylcholination interfered with Rab1 activity by making it less accessible to the bacterial GTPase activation protein LepB; this interference can be alleviated fully by Lem3. Our results reveal reversible phosphorylcholination as a mechanism for balanced modulation of host cellular processes by a bacterial pathogen.